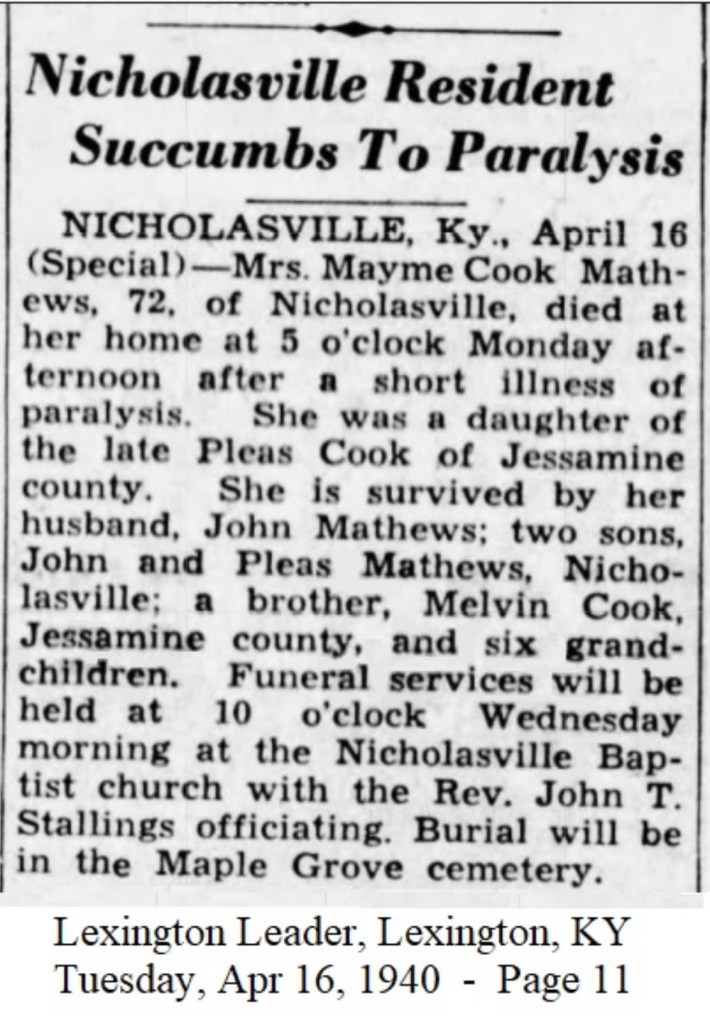

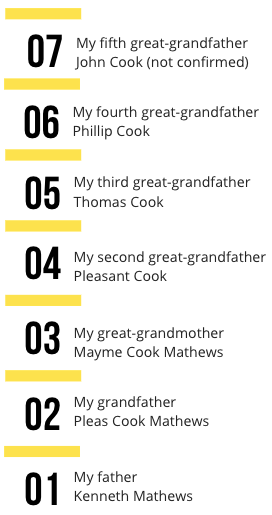

My grandfather, Pleas Mathews, died from osteomyelitis, a kind of staph infection of bone, reportedly contracted during WWI service while marching with US forces in Germany in worn-out boots and open sores on his feet. I wonder could there have been a parasite or exposure to chemicals? This was back before penicillin. Pleas was with the First Pioneer Infantry-Company I from June 1918 – July 1919, soldiers who built bridges, roads and maintained railroads just behind the front lines while maintaining combat readiness.

A well-written account of the First Pioneer Infantry in WWI can be found here in full text. And, I found a photograph of soldiers clearing a road in France in the same period my grandfather was serving there. The visual is powerful in alighting my imagination and the narrative follows Pleas’ journey in detail.

The family lore, if you will, consists of a reported medical study of Pleas’ collar bone regrowth, and the harsh realities in gradual progression of the overall physical toll from his illness or illnesses. Dad says Pleas had open sores over his body and his bones were routinely scraped down then packed with some substance leaving the sores exposed. He cringed as he recalled living with the smell of his father’s rotting bones and flesh. He recounted a story when Pleas bought some snake oil from a salesman in town that Dad said was nasty to taste or smell. They had no idea what was in it and he remembers how that bottle sat up on the shelf afterwards. Later, Pleas improved after receiving a trial of penicillin. His life was saved with the introduction of penicillin but the long-term effects of his illness were a plague for the remainder of his life.

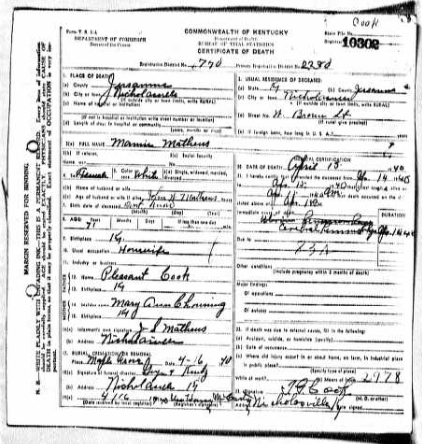

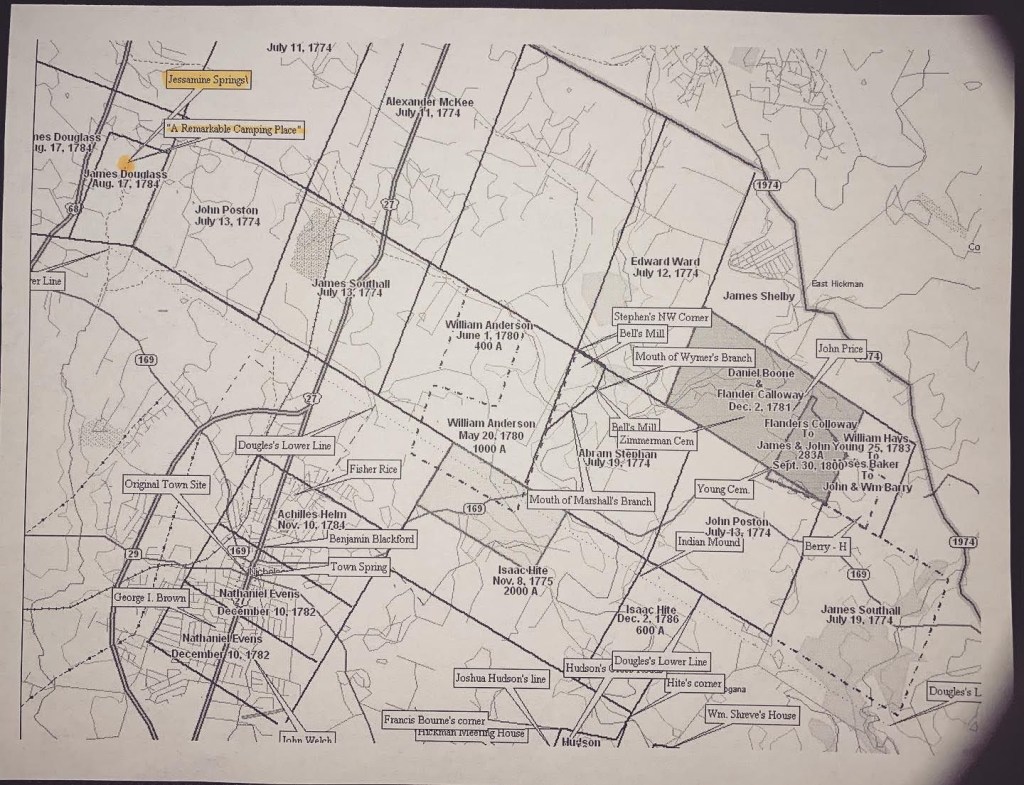

I’ve found few definitive details about his illness. One source is his WWII draft card I found on ancestry.com and in our family’s archival collection. Dated April 27, 1942, he was a light complexion, 47yo white man with brown eyes, brown and gray hair, weighing 130lbs at 5’7 1/2″ tall. Local (draft) Board No. 88 Jessamine KY registrar, Opal N. Finnell, notes as “Other obvious physical characteristics that will aid in identification” and her handwritten response, “Disabled soldier of last war Collar bone removed.” There are numerous itemized medical bills and receipts of payment during the period of 1946-1953. The pattern of treatments over time tell a grim story for his remaining years. Pleas died in 1955.

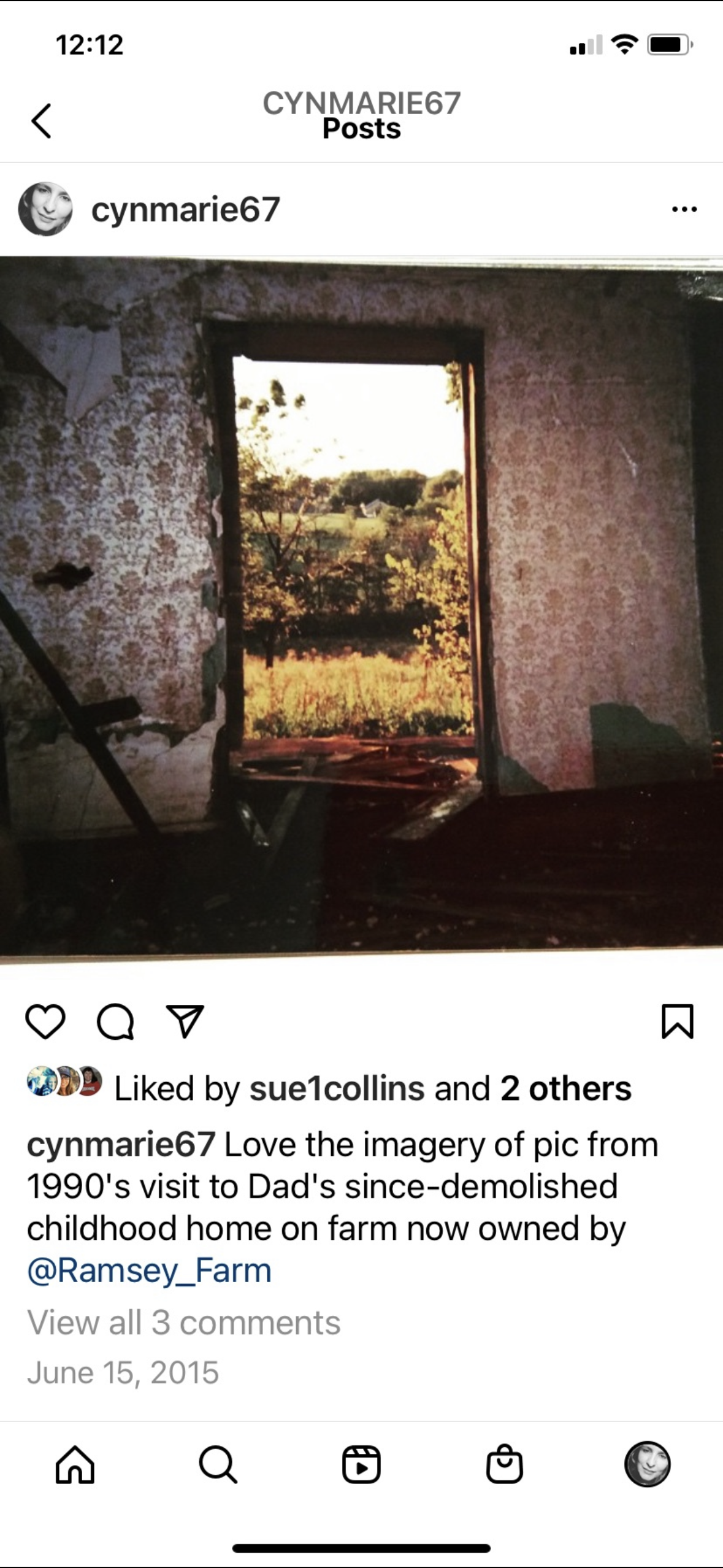

I cannot begin to imagine the life of my father in his youth and now regret not being more mindful of every detail he’s ever shared about those years on the ol’ homeplace. He grew up working tobacco on the family farm with his siblings, cousins, neighbors and, for a brief time, with German POWs. Hard working, hard living. A work ethic that epitomizes the definition of the term. Up early to work the farm, off to school, back home to finish chores. Do again the next day. I think of how I get “worn out” from some housecleaning or yard work and his daily life required both kinds of labor plus schooling. That book learning was a Mathews core value.

Pleas lost some use of his arm following the removal of his collar bone. This leaves many unanswered questions, including was this due to an injury from combat? Being the head of the household with limited dexterity, Pleas daily faced physical challenges of maintaining a farm, producing both cash crops and food for the family and farm animals. My dad was the son chosen to labor as literally serving at and as the hand of his father.

Dad said Pleas would cite Bible verses from memory throughout their working hours. Knowing what little I know as a modern-day understanding of PTSD, clues like this make me wonder about his state of mind and whether he suffered the same. The nature of their family dynamics is infinitely intriguing to me through the lens of a soldier’s return home.